by Dastan Galali

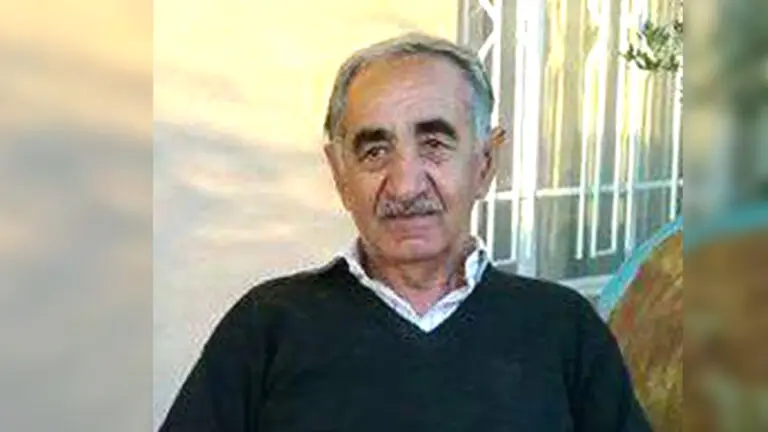

Whenever someone discusses the art of translation into the Kurdish language, Aziz Gardi (1947 – 2022) comes to mind. As the most prominent Kurdish translator, his name is familiar to any Kurdish reader who reads in the Sorani dialect. Gardi’s translated works—he translated approximately 200 books, most of them literary—have consistently been best-sellers, thanks to his rich, clear, and precise language, as well as his catchy phrases. His enchanting language earned him literary acclaim among the Kurdish intelligentsia.

Gardi’s Innovations

Hailing from a small town near Hewlêr (Erbil), Gardi began his literary career at an early age while writing a book on rhetoric in Kurdish literature—the first of its kind—in 1968; it was published in 1970. His first published translation appeared in 1976 by the Kurdish Academy Center in Baghdad. It was a novella titled Three Drawings by Alexei Balakayev, which he translated from English (Rasul 2021, 1556).

After that, he translated many world masterpieces and mastered five languages: Kurdish (both Sorani and Kurmanci), English, French, Arabic, and Persian. Among his notable literary translations are Rasul Gamzatov’s My Dagestan, Dante’s Divine Comedy, Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, Aristotle’s Poetics, M. B. Rudenko’s Kurdish Mythology, and the Brothers Grimm’s Fairy Tales.

Gardi introduced many renowned literary figures to Kurdish readers—such as those mentioned above—at a time when books in the Kurdish language were rare and no Kurdish institute or college existed. He faced numerous challenges in his early works, including the absence of a proper Kurdish dictionary and a shortage of books translated into Kurdish, particularly from Western languages. He essentially started from scratch.

His translations are known for their poetic language combined with everyday expressions, a result of his extensive reading and deep understanding of literature, as well as his meticulous attention to language. For example, in an interview with a friend, he mentioned that he reviewed his translation of My Dagestan more than ten times and still was not satisfied with it (Qaraman 2023, 100). On one occasion in 1982, he traveled 46 km just to find the right words while translating The Kurdish Woman’s Life by Henny Harald Hansen (Rashid 2023, 14). He made many sacrifices during his career; once he told a friend, “If you want your work to be immortal, you have to sacrifice your life for it” (Dashti 2023, 21).

His translations are known for their poetic language combined with everyday expressions, a result of his extensive reading and deep understanding of literature, as well as his meticulous attention to language. For example, in an interview with a friend, he mentioned that he reviewed his translation of My Dagestan more than ten times and still was not satisfied with it (Qaraman 2023, 100). On one occasion in 1982, he traveled 46 km just to find the right words while translating The Kurdish Woman’s Life by Henny Harald Hansen (Rashid 2023, 14). He made many sacrifices during his career; once he told a friend, “If you want your work to be immortal, you have to sacrifice your life for it” (Dashti 2023, 21).

For Gardi, translation was more akin to rewriting or even inventing a new work. “Knowing a language does not mean you can translate it. Translating is inventing a new work, like any piece of literature,” he noted (Qaraman 2023, 74). Once he narrowly escaped assassination by radical Islamists due to his translation of The Kurdish Women, a component of The Women of Turkey and Their Folk-Lore, by Lucy Garnett. The book includes a story about mullahs that highlights the greed of some mullahs—which incited extremist mullahs to plot his assassination. Fortunately, a friend of Gardi, aware of the plot, warned him and saved his life (Qaraman 2023, 81). These episodes illustrate Gardi’s dedication to the art of translation; he put his heart and soul into it, a level of commitment that is rarely seen.

Gardi coined many words in Sorani through his translations. Some of the words he coined are: پێشخزمەت for garçon, وارخان for apartment, هازی for energy, خێراکار for computer, کۆڕی زانیاری for academy, زانستگایی for academic, تەکووز for perfection, کەتوار for reality, بەرژەنامە for form, ڕۆنڤیسین for copy, شابەندەر for consulate, بەرزەفت for control, and گژنێ for challenge.

Throughout his career, Gardi influenced many individuals to pursue the path of translation. Azad Berzinji once revealed that he had been inspired to consider a translation career after reading My Dagestan, which impressed him with its poetic language (Berzinji 2023, 9). Atta Qaradaghi recounted how Gardi encouraged him to embrace the art of translation during his early college days in the English department: “One day Azizi Gardi came to me, opened his bag, and gave me an English book to translate. I told him, ‘I can’t do it. I’m just a freshman.’ He insisted that I should translate it and that he would revise it. So I translated the book, and Gardi showed me what was wrong with my translation. This is how I became a translator” (Qaradaghi 2023, 27). Adeeb Nader, another prominent Kurdish translator, acknowledged that Gardi’s translations played a significant role in his decision to start his career (Nader 2023, 64). Gardi himself was notably inspired by Masoud Muhammed, Hazhar Mukriyani, and Alaaddin Sajadi, all of whom are esteemed Kurdish writers.

Gardi’s National Stance

In 1975 a man named Hameed Abdulla Kakawais asked Gardi to translate Aziz Nesin’s Zübük, but Gardi refused due to Nesin’s attempts to Turkify Kurdish people by teaching the Turkish language to Kurds in Turkey. His refusal indicates that Gardi had strong national feelings. “Gardi always distanced himself from writers affiliated with the Iraqi Ba’ath Party and warned me not to befriend them,” one of his close friends said (Rashid 2023, 13).

At times, he wrote under pseudonyms to avoid detection by the Ba’ath regime. In the early 1970s, he translated Mahmoud Darwish’s poem “The Kurd Has Nothing but the Wind” under the pseudonym Rawchi. It was published in Baraw Runaki magazine in Hewlêr’s Galala subdistrict.

Additionally, Gardi did not affiliate with any Kurdish political party; he remained independent throughout his life. He believed one could serve their nation without direct involvement in politics. He thought the best way he could benefit an oppressed nation was through writing and translation, considering the pen the most effective weapon to fight against Kurdish oppressors. Had it not been for him, we would not have these magnum opuses in the Kurdish language.

The Loneliest Kurdish Writer

Gardi lived in solitude throughout his life. I personally haven’t seen any Kurdish writer as lonely as he was. So dedicated to his writings was he that when a close friend asked him to get married, he responded, “My books, my library is my wife” (Rashid 2023, 13). Although he had a sense of humor, he was very sensitive, especially when questioned about his personal life. He also didn’t like compliments, a characteristic we rarely see among writers.

Another factor contributing to his loneliness was his suspicion of people. When asked why he was so suspicious, he said, “People say that I can’t get along with anyone, but that’s not true. If someone is an honest person, I will be his servant. But I became so frustrated and depressed when I see one of my best friends turn out to be unfaithful to me. That’s why I’m very careful in approaching people. If someone is unfaithful, why should I befriend him?” (Qaraman 2023, 90). This reveals that he was not a sociopath or misanthrope, but a man whose encounters with many dishonest individuals made him cautious about connecting with others.

Another factor contributing to his loneliness was his suspicion of people. When asked why he was so suspicious, he said, “People say that I can’t get along with anyone, but that’s not true. If someone is an honest person, I will be his servant. But I became so frustrated and depressed when I see one of my best friends turn out to be unfaithful to me. That’s why I’m very careful in approaching people. If someone is unfaithful, why should I befriend him?” (Qaraman 2023, 90). This reveals that he was not a sociopath or misanthrope, but a man whose encounters with many dishonest individuals made him cautious about connecting with others.

His solitude can be compared to that of Emily Dickinson or J. D. Salinger, whose creativity led them to loneliness.

Gardi’s Academic Career

In addition to being an excellent translator, Gardi was also an accomplished academic writer. In 1968, when he was only 21 years old, he began writing a book titled Rhetoric in Kurdish Literature (1970), in which he utilized English and Arabic rhetoric. This book is considered the first Kurdish work on rhetoric in literature.

In the 1980s he earned a bachelor’s degree in French language at Mosul University. Meanwhile, he completed his master’s degree in Kurdish literature in 1994 at Salahaddin University in Hewlêr, with his thesis entitled “Kurdish Classical Meters Compared with Arabic Prosody and Persian Meters: An Analytic Comparative Study.” His Ph.D. dissertation in the same field, completed in 1999, was titled “Rhyme: An Analytic Comparative Study in Kurdish Poetry.”

He earned his second Ph.D. in English Literature at Koya University in 2009. This dissertation, entitled “Romeo & Juliet and Mam & Zin: A Comparative Study,” compares various aspects of the two literary masterpieces and also includes translations of Romeo and Juliet into Sorani and Mem û Zin from Kurmanci into English.

Here we take a quick look at both translations.

Two Translations by Gardi

The Translation of Romeo and Juliet into Sorani

Here is a brief excerpt from Act 1, Scene 1:

The Text in English

Sampson: Gregory, on my word, we’ll not carry coals.

Gregory: No, for then we should be colliers.

Sampson: I mean, an we be in choler we’ll draw.

Gregory: Ay, while you live, draw your neck out of collar.

Sampson: I strike quickly, being moved.

Gregory: But thou art not quickly moved to strike.

Sampson: A dog of the house of Montague moves me.

Gregory: To move is to stir; and to be valiant is to stand.

Therefore, if thou art moved, thou runn’st away.

Sampson: A dog of that house shall move me to stand. I will

take the wall of any man or maid of Montague’s.

Gregory: That shows thee a weak slave, for the weakest goes

to the wall.

Literal translation

سامسۆن: گریگۆری، سوێند بێ، خەڵووز هەڵناگرین

گریگۆری: نەخێر، دواتر دەبین بە کرێکاری خەڵووز

سامسۆن: مەبەستم ئەوەیە ئەگەر تووڕوشبین، شمشێر هەڵدەکێشین

گریگۆری: ئەی، مادام دەژیت، ملت لە یەخە دەربێنە

سامسۆن: بە خێرایی ڕایدەوەشێنم گەر بجووڵێی

گریگۆری: بەڵام تۆ بە خێرایی ناجووڵێی بۆ ئەوەی ڕایبوەشێنی

سامسۆن: سەگی ماڵەکەی مۆنتیاگۆش دەمجوڵێنێ

گریگۆری: بجوڵێی واتە هەڵدەجی، بشمێنیتەوە واتە ئازای. بەڵام تۆ هەر کە بجوڵێی ڕادەکەی

سامسۆن: سەگی ئەم ماڵە دەمجوڵێنێ. هەموو دیوارێکی پیاو یان خزمەتکاری مۆنتیاگۆ دەستبەسەردا دەگرم

گریگۆری: ئەوە نیشانەی ئەوەیە کە تۆ کۆیلەیەکی زۆر بێ هێزی چونکە تەنها بێ هێزەکان بن دیوار دەگرن

Gardi’s translation

سامسۆن: بەڵێن بێ! ڕەژوو نەکێشین.

گریگۆری: نەخێر، ئەگەر وا بکەین دەبین بە ڕەژووکەر.

سامسۆن: مەبەستم ئەوەیە ئەگەر تووڕەبین، شمشێر هەڵدەکێشین

گریگۆری: بەڵێ، مادام دەژی، دەبێ ملت لە یاخە بێنیتە دەرەوە (خۆت لە گێچەڵ دووربخەوە).

سامسۆن: ئەگەر بڕووژێم، زوو دەست دەوەشێنم.

گریگۆری: بەڵام تۆ زوو ناڕووژێی تا دەست بوەشێنی.

سامسۆن: سەگی بنەماڵەی مۆنتاگیۆش دەمرووژێنێ.

گریگۆری: برووژێی، واتە هەڵدەچی. ئازا و بوێر بی، پێ دەچەقێنی. بەڵام تۆ ئەگەر بڕووژێی، ڕادەکەی.

سامسۆن: سەگی ئەم بنەماڵەیە دەمڕووژێنێ بۆ ئەوەی پی بچەقێنم: من بن دیوار لەهەر پیاوێ یان خانمێکی بنەماڵەی مۆنتاگیۆ دەگرم.

گریگۆری: ئەمە دەری دەخا کە تۆ بەندەیەکی زۆر بێ هێزی، چونکە ئەوەی هەرە بێ هێز بێ، ئەو دەچێتە بن دیوار.

The Translation of Mem û Zin into English

Here is a short excerpt from Gardi’s translation of Mem û Zin into English:

The Text in Kurmanci

Saqî! Tu jibo Xwedê kerem ke

Yek cir’e meyê di camê Cem ke

Da cam-i bi mey cîhannuma bit

Herçî me îradeye xuya bit

Da keşf-i bi bit h ber me ehwal

Kanê di bitm miyesser îqbal ?

îdbarê me wa gîha kemalê

Aya buwe qabilê zewalê?

Ya her v/ehe dê Ii îstîwa bit,

Hetta wekû dewrê minteha bit?

Qet mimkune ev ji çerxê lewleb:

Tali’ bi bitm jibo me kewkeb,

Bextê me jibo mera bi bit yar

Carek bi bitm ji xwabê heşyar

Literal translation

Bartender! Please come to me.

Pour a drop of wine to my glass.

It reveals to me the secrets of the world.

Even though we have a will to be seen.

To discovery of the little things to us.

Where is the best of the best?

Our mind is the root of perfection

Is it ripe for harvest?

Or will it always be so,

Even as the time of the moon is so?

Is it possible that this is a cycle of change:

The tide is turning for us,

Our luck is turning for us

Once we wake up from a dream

Gardi’s translation

O cup-bearer, please for Allah’s sake,

Pour out a single dose of wine into (Jam)’s cup.

So that the cup may show us the world

It may manifest whatever we desire.

The states may be disclosed for us

To see whether the luck will be obtainable?

Our calamity reached its highest point,

Is it now terminable?

Or it remains at the equator,

Until the end of the turn?

Is it possible that the fortune-planet

May rise up upon us from the revolving universe?

Our luck may make friends with us,

It may once awake from the slumber?

Dastan Galali is a literary translator and academic based in Hewlêr.

Dastan Galali is a literary translator and academic based in Hewlêr.