Kurdistan Center for Arts and Culture (KCAC)

On a day in January 2024, speaking via Zoom from his office in Erbil, Muhammad Fatih told the NYCCC that Kurdistan must do a better job of preserving its written heritage. In the KRG alone, he said, some 100,000 old manuscripts exist, scattered across numerous private and public institutions, but “a lot of them are at risk of deterioration because of lack of proper storage.” These manuscripts represent a major part of Kurdish heritage, he said, and should be cared for properly—curated and preserved for future generations.

But Kurdistan lacks institutions that are adequate for preserving that heritage, so he decided to found one himself. He would gather a team of people who shared his belief, and together they would work to acquire and equip a building to store and handle archives. Then they would inviting those who possessed deteriorating manuscripts to donate them, where they could be restored and preserved.

In 2022 Fatih founded the Kurdistan Center for Arts and Culture (KCAC), a nongovernmental organization is based in Erbil, with a satellite office in Slemani. A year later, he and the team he assembled area still working on acquiring a physical space. They’ve applied for a parcel of land, and it’s still pending.

Archive

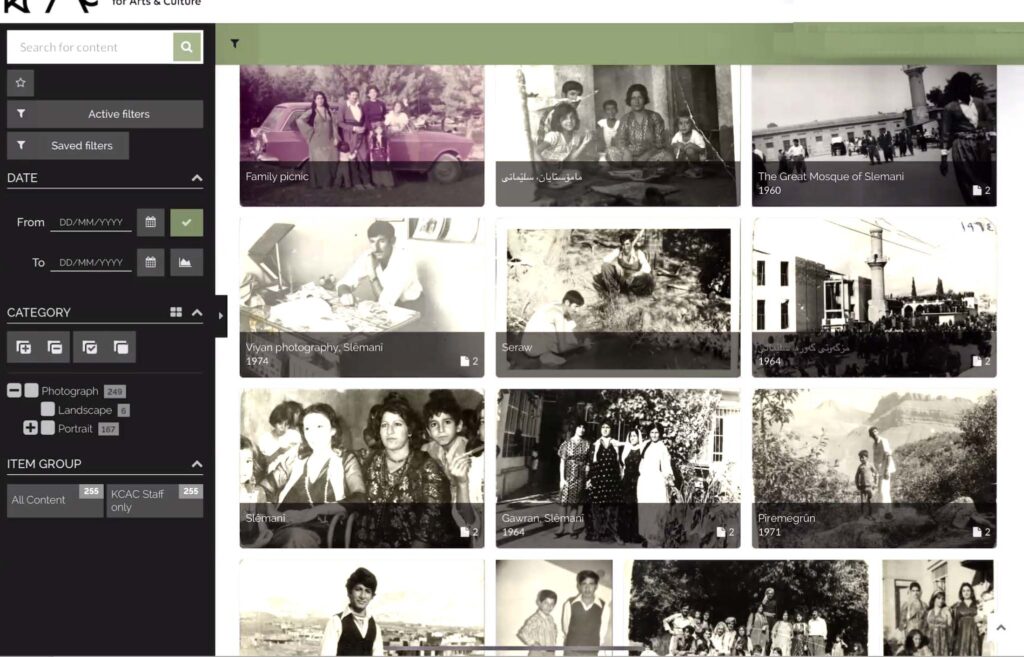

In the meantime, they are moving forward. They have created a digital archive to go with the physical space. It opened in May 2024. Here the manuscripts, in digital form, can be cataloged, organized, and made accessible. They hope the archive, based in Kurdistan, will become a global platform for the preservation and promotion of Kurdish culture and art.

The archive at this point covers only Iraqi Kurdistan (Bashur), but the team intends to expand to other parts of Kurdistan as the KCAC grows, especially to Rojhelat, where the borders are permeable. But for now they concentrate on the KRG.

A team of five young Kurds acquired a van and specially equipped it with advanced scanners manufactured in Germany and Japan, suitable for archival purposes. “None of us is a specialist in archiving, so we had to bring in international trainers,” Fatih explained. That’s how they learned to use the scanners and the accompanying software.

They seek out local collectors or archivists, people with a collection of documents, periodicals, photos, and the like that are at least 30 or 40 years old. They are often much older. They meet up with the collector. Some are local archives; some are individuals, like the man in Rojhelat who has a copy of the Koran on which Qazi Muhammad was sworn in as head of the short-lived Mahabad Republic. The team regard it as crucial to build a good relationship with the collectors they work with. They study the documents and select the ones they wish to archive.

On an appointed day, the team shows up in the van and create high-quality, high-resolution scans. Then they upload them into the system. They note the language, author, translator, place of publication, date, category, source tag, and so on. They’re careful to register the metadata. “We always credit the collection source,” says Fatih, whether public or private, and individual or a library or another archive. “It’s part of how we build trust—we immortalize your collection.”

The team works slowly, carefully, and methodically—sometimes it takes them a week to digitize only 40 items. But in the end the scans become part of the online archive that the KCAC is building in accordance with international library standards. It’s accessible in three languages. They are striving to make it easy to use for researchers. “We’re even working on adding a face recognition feature, so that when a face is identified an tagged, the user can search for that person,” Fatih explains.

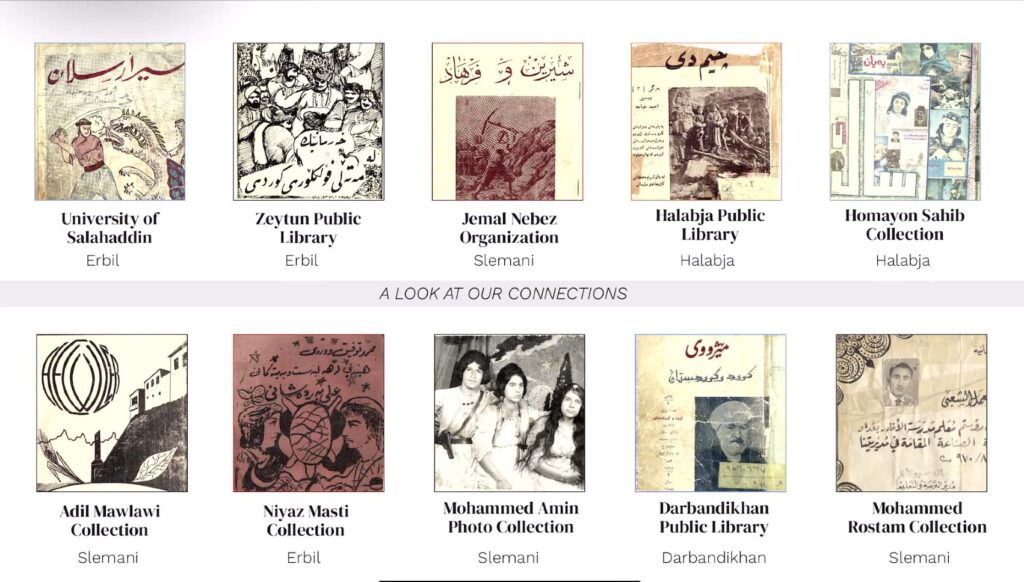

They’ve already organize several collections. One is a set of digitized photos of Silêmanî. Another is the collection of Safi Hirani, a Sufi sheikh and classical Kurdish poet—his descendants allowed the KCAC to archive it. Another collection comes from the Central Library of University of Salaheddin, and another from the Zeytun public library.

Because of the meticulous tagging, all the items are searchable. The search engine includes an OCR feature that detects text in different Kurdish languages. In another feature, a user can highlight a portion of a document, and a rough translation into English will appear on the sidebar. That makes it useful for international researchers.

So far they have digitized 736 items and hope to make it to 1,000 by the opening in April 2024. Once the digital archive is live, they intend to promote it to public and private universities, for scholars to access. Within Kurdistan, Kurds will be able to access it through their local libraries. Abroad, universities will be able to subscribe to it. They are eager to interest universities with Middle Eastern studies departments. Once they collect subscription fees, they will plow them back into the archive to expand it further.

Exhibitions

Another component of the KCAC’s program is art exhibitions. Drawing on the archive, they are planning exhibitions of poetry manuscripts, and of copies of the Koran from Kurdistan, and maps, and more.

Several of the existing online exhibitions involve photojournalism, mixing text and photos. “Hiking Mountain Paths” features work by the UK photojournalist Emily Garthwaite, telling stories of Kurdish village life. “Following the Steps of Nomads” exhibits photos by Shamal Hismadin. “Weaving the Story of Kurdish Clothing” displays photos by Omer Nihad. “Capturing the History Kurdish Photography” highlights the work of Muhammed Amin.

They intend to mount 10 photojournalism projects a year.

In terms of subject matter, the KCAC stays away from politics and conflicts, instead emphasizing culture. Too often Kurds have been recognized for their fighting ability, Fatih points out, but the KCAC wants to show the world that in Kurdistan, “there is a life beyond war.”

The KCAC is also planning to hold a series of workshops for filmmakers. They will bring screenwriters, producers, and sound engineers to Kurdistan to train Kurds in cinema arts and technology. In this respect, they are currently working with the Polish documentary filmmaker Anna Zamecka. “Anna has been helpful in internationalizing local talent,” they explain.

Translations

The KCAC also translates and publishes significant Kurdish works that have been overlooked internationally. Although the translations are intended for a global readership, the KCAC hopes to focus specifically on writers that are important to Kurdish people themselves. “We’re translating not what westerners would want but what’s important to Kurds,” Fatih explains.

So far they’ve translated and published the autobiography of Hejar Mukriani, Food of the Mosque Servant.

Public Projects and Advocacy

The KCAC sees itself as a think tank for the preservation and promotion of Kurdish art and culture. KCAC members are part to the restoration team, for example, that’s restoring the Grand Mosque of Khurmal.

In addition to promoting Kurdish culture, the KCAC is trying to create a culture of preservation by training a new generation of archivist to meet high professional standards. “Cultivating human resources is as important as the work itself,” says Fatih.

The KCAC has large ambitions, but they have made impressive progress in only one year. Fatih recommends that you follow the KCAC on Instagram. “There you can see how we work, … young people involved in building one of the most important institutions in Bashur.”