by Kamal Soleimani

Kurdish language, poetry, and literature in general are filled with enduring stories of Kurdish communal life—marked by hardships, struggles for survival, and rebellion against despair and injustice—that reflect Kurds’ tenacity to live and resist the conditions of a securitized existence under colonizing sovereign powers. In the north, the daily ritual of reciting the Turkish national anthem forces every Kurdish schoolchild to sing in Turkish: “May my life be a gift to the Turks’ existence.” As a result, their voices and bodies must constantly resist being claimed by “others, others’ nationalist norms, social and political organizations,” as well as the dominant interpretation of their religions, which demands their ungrievable existence, to use Judith Butler’s phrasing. Thus, Kurds are constantly required to renounce their rights, their soverignity over their bodies, and their collective self, and embrace collective self-sacrifice “in order to minimize precariousness for others.”

The Kurdish community possesses a profound awareness of its own plight. Kurds recognize their status as the “orphans of humanity,” a condition that renders their perpetual displacement to seem almost normal. They perceive that the entire world bears some responsibility for their suffering, which is a shared phenomenon among them. Consequently, their humor, often laced with a unique form of theological irony, reflects a belief that even God seems to avoid or is incapable of addressing the Kurdish question.

This sentiment becomes particularly pronounced in South Kurdistan under Iraqi rule, especially after the genocide perpetrated by the Iraqi state, where a brand of dark theological humor emerged. This humor has found expression in poetry, literature, and popular jokes, capturing the tragic essence of Kurds’ experiences. The widespread slaughter of hundreds of thousands of Kurds by the Iraqi state is mirrored in these jokes, suggesting that the Kurdish question poses a dilemma for the modern world—one that appears unsolvable, both in this life and possibly in the next.

In satirical narratives, even divine mercy seems conditional. The humor implies that God favors His “chosen people,” yet Kurds are sacrificed for the greater good of others. This bleak perspective encapsulates the harsh reality of Kurdish existence, highlighting a belief that God has turned a blind eye to Kurdish reality, as illustrated by the following joke, common in South Kurdistan:

In the day of resurrection, God declares that the Kurds can enter paradise without questioning, for they had already lived in hell in the previous world. As they enter Paradise, the Kurds, true to their old habits, begin dancing and singing. This exuberance prompts the other inhabitants of paradise to become annoyed by the sounds of the Kurdish language and the Kurds’ spirited performances. Frustrated, they complain to God about the Kurds’ presence in Paradise. In response, God expels the Kurds—reminding them of Adam’s story and the ensuing infinite human tragedy—and sends them to hell.

Yet, adhering to their secret of survival, the Kurds once again turn to their songs and dances to mark their new life. The inhabitants of hell, faced with the Kurds’ presence, become oblivious to the daily death, fire, and misery, quickly beginning to complain to God. In light of the Kurds’ antics, God acquiesces to the wishes of the people of hell and expels the Kurds, sending them to purgatory.

Upon their arrival in purgatory, the Kurds revive their tradition of singing in Kurdish and dance for days. Eventually, God notices the unusual silence among the Kurds and grows curious: “Where are these noisy Kurds?” he asks a little boy. “Oh uncle, the Kurds have found their old job—they’re smuggling people from hell into Paradise.” In smuggling criminals from hell to Paradise, the Kurds finally take their revenge on God and his beloved servants.”

This form of theological irony appears frequently in literary tropes, poetry, and Kurdish humor. As noted, it serves as an idiom of resistance: a cry against injustice and a complaint about the extraordinary condition of the Kurds, while simultaneously declaring stubbornness and resolve. To illustrate how this resistance is narrated and reflected in the Kurdish language, I will briefly discuss three poems written by three legendary Kurdish poets.

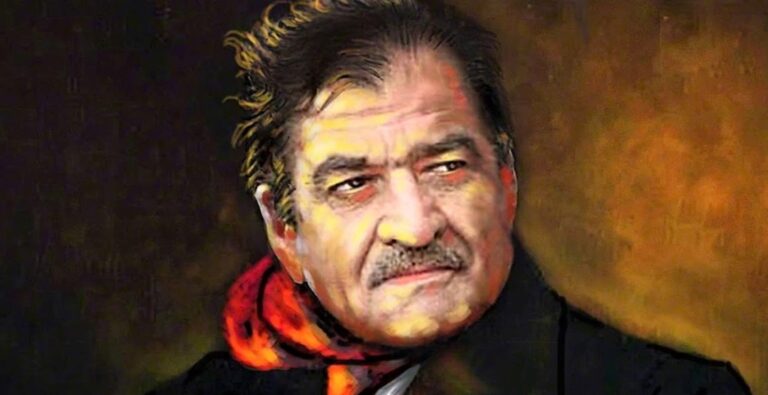

Sherko Bêkas (1940–2013) in a poem fearlessly mocks Islamic theology for its colonizing tendencies, revealing God’s indifference in the face of Kurdish genocide. In Bekas’s view, the Muslim God remains aloof, untouched by the suffering of Kurds. He criticizes dominant Muslim theologians, who have anthropomorphized and ethnicized God, reducing the divine to a narrow, ethnocentric construct. From Bêkas’s perspective, the monotheistic theology of Islam, which claims to treat all Muslims equally, instead portrays God as an ethnocentric deity—deaf to the pain and pleas of Kurdish Muslims, whose voices are stifled by their supposedly “undecipherable” tongue. For Bêkas, this was painfully evident following the chemical bombing of Halabja in 1988. A Muslim summit convened just days after this horrific event, yet Halabja went unmentioned. Either the God of Muslims has no concern for Kurdish believers, or the language barrier between Kurdish Muslims and God renders their cries unheard.

In them poem “A Lengthy Letter to God” (translated by Alana Marie Levinson-LaBrosse and Halo Fariq), Bêkas pens a personal letter to God, only to find it barred from reaching the Almighty. In the vast expanse of divinity, it seems, no one understands the Kurdish language. As the poem reveals:

After Halabja suffocated,

I wrote a long complaint to God

Before everyone,

I read it to a tree.

The tree cried.

From one side, a bird, a postman,

Said, “All right, who will deliver it?

If you are expecting me to take it,

I won’t reach God’s throne.”

Late that night,

My angelic poem, dressed for mourning,

Said, “Don’t worry.

I will take it to the heights

Of the atmosphere.

But I won’t promise

He will take the letter Himself.

You know, the Great God

Who can see Him?”

I said, “Thank you. Fly.”

My angelic inspiration flew

With my complaint.

The next day, it was returned.

God’s fourth secretary down,

A man by the name of Obaid,

At the bottom

Of the very same complaint,

Wrote to me in Arabic:

“Idiot, make it Arabic.

People here don’t know Kurdish.

They won’t take it to God.”

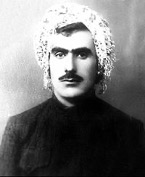

Unlike the atheist Bêkas, Hajar (1921–91) was a religious scholar who transformed the question of the Kurdish language into a theological one, creating what could be seen as a linguistic theology of resistance.

For Hajar, Kurdish self-identification was an act of resistance, a protest, and a poltical form of self-assertion. He famously wrote:

I live as a Kurd,

die as one,

will rise again as a Kurd

to defend Kurdish rights

in the world that follows this one.

In 1957, Hajar penned a poem that fundamentally challenged Muslim rhetorical colonialism, which often disguises itself as religious brotherhood while denying the rights of dominated communities like Amazighies, Baluches, Kurds and on on, relegating their language, history, and self-identifican to the realm of non-existence.

In the poem “Talqeen in Kurdish” (Talqueen be Kurde), Hajar criticized dominant Islamic theology as a theology of exploitation, urging Kurds to resist even the angels of God who demand that they speak in Arabic after burial. A talqeen is a sermon typically delivered by an imam after a Muslim’s burial, where the basic tenets of Islamic theology are reiterated in Arabic to the deceased. Interestingly, the addressee is the buried individual, instructed on how to respond when questioned by two angels who are said to visit after the burial site is vacated. Hajar turns this theological message for the dead into a call for Kurdish resistance. He declares:

O servant of God, son of the worker,

Listen from within your narrow grave,

You have departed this unfair world,

And now taken a house in eternity.

Two angels of God will visit you,

With yellowed teeth and blood-red eyes,

Carrying hammers and metal scales,

They will strike you, frail and broken,

But they’ll say, “Speak, we come with questions.”

No matter how many times they ask, “Where is your answer?”

Stay silent, do not get angry, make no sound.

If they taunt you, spitting upon you,

Say, “I am a Kurd; no tongue I know.”

Do not fear their threats or heed their insults;

Force them to speak in Kurdish.

Now, in the sweet language of Kurdish,

Do not falter—take your time, and say:

God, the Prophet, and His truth are clear,

Kurdish is simple; the language imposed upon us is difficult.

Speak of death and resurrection,

But do not lose yourself for nothing.

Say: “Kurds have been dead for a very long time,

Their Judgment Day had come before their birth.”

Without clothes, without shoes, without bread or wealth,

Muslim states devour them,

While Kurds are oppressed and the powerful feast—

Brothers in faith, yet the Kurds are exploited.

Ask God: “If this is truly religion,

Is it just our burden, words, and deception?”

If religion denies Kurds’ rightful place,

No matter how sublime,

I would trade it for less than a dime.

The Kurdish language, in particular, rejects the rhetorical colonialism that seeks to alienate Kurdistan from the Kurds or de-Kurdify its sapace and history. Through linguistic references, the Kurdish language actively resists this erasure, opposing the reworlding of Kurdish geography. Kurds persistently strive to affirm the Kurdistaniness of their land and restore themselves to the center of their homeland. Kurdish sustains the sense of home and keeps the historical narrative alive and enduring.

The international borders between Iran, Iraq, Syria, and Turkey have forcibly divided Kurds and their historical homeland. This division has reshaped the very meaning of border and borderland. From the Kurdish perspective, the borders imposed a century ago—against Kurdish wishes—are colonial constructs.

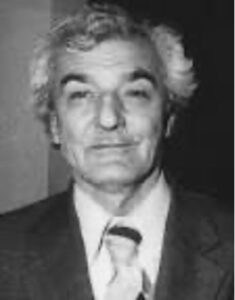

Consequently, Kurds refuse to recognize these borders as markers of their identity, as the iconic Kurdish poet Hêmin Mukryani (1921–86), poignantly illustrates:

It separates me from you,

It separates me from you,

hides you from me,

The little inch which is called the border

It was defined by my enemy.

Through their language and daily geographical references, Kurds resist the historical imposition of these borders. This refusal is enacted continuously through the Kurdish language. Kurdish geographical terms for the four parts of Kurdistan—Bakur (the North), Bashur (the South), Rojava (the West), and Rojhelat (the East)—represent Kurds’ ongoing (re)Kurdification of their indigenous geography. The language itself becomes a powerful symbol of the Kurdish narrative.

These references are not only acts of remembrance but also acts of resistance, expressed through oppositional identification. They are rhetorical and radical exercises of sovereignty, tantamount to everyday decolonization. While the colonial borders have divided, constricted, and fragmented Kurdish identity, Kurds, through their language, regard what others call the borderland, borderlines, or border zones as the heart of their torn nishtiman (or homeland).◊

Except as indicated, the lines of poetry quoted were translated by the author. In Hajar’s poem, references to God as Arab, Persian, or Turkish have been replaced with a more universal, ethnically neutral depiction of God, to preserve the intended meaning while being sensitive to diverse interpretations.

This text was prepared for a panel presentation at the New York Kurdish Film Festival, 8th edition, in November 2024. The author would like to express sincere gratitude for the exceptional work of the event organizers, particularly Xeyal Qertal and Janet Biehl, whose dedication and efforts made this festival a resounding success and a source of pride for all the participants.